Anya Liftig and Andrea Kleine, My Dinner with Andrea: the Piece Formally Known as Torture Playlist (2017). New York Live Arts.

Photo: Paul B. Goode, Courtesy of Andrea Kleine

By Daniella LaGaccia

I didn’t meet Andrea Kleine and Anya Liftig at a restaurant like the Café des Artistes in the Upper West Side, but we did find a nice coffee shop off the corner of Bryant Park. Pop music from the radio filled the room, dishes scrapped and the chatter of after work patrons bled into my recorder.

I interviewed both Andrea Kleine and Anya Liftig in May about their performance, My Dinner with Andrea: the Piece Formally Known as Torture Playlist last March at the New York Live Arts center. The performance had several stages, beginning in the lobby where musicians Michael Kammers, Bobby Privet, and Neal Kirkwood played the theme to Rawhide while the audience was still waiting to get into the theater. Alison Inglestorm then took the spotlight, repeating a dance routine to the pop song Call Me Maybe by Carly Rae Jense. Inglestorm led the audience in the theater, repeating the routine to the song, and then finally dropping to the floor in exhaustion. Anya Liftig begins to speak. She’s recount her life as a performance artist and walks to a table that has been set up in the center of the stage. Andrea Kleine meets her there, and then they begin to have a conversation about life, torture, high school plays, and Florida.

It should be noted that this interview references quotes from an interview Andrea Kleine and Anya Liftig published for Movement Research last March, and it references scenes and lines from the 1981 film, My Dinner with Andre. This interview also talks extensively about the “torture playlist”, songs used by the CIA to torture terrorist suspects. An article about the playlist can be found here.

Daniella LaGaccia: You said you were at an artist residency recently, what have you been up to?

Anya Liftig: I was at MacDowell [The MacDowell Colony] and that’s where I met Andrea and Bobby [Previte]. I was there trying to make video work and some 2D work, and blowing things up large. I was also doing collage work, not necessarily performance.

Andrea Kleine: I think it was 2013, and I was working on a novel there, but I think I already had that gig at The Chocolate Factory scheduled, I must of, so I had taken this long break from making performance work, and then I was sort of coming back to it. One thing I wanted to do with going back to performance, was that I didn’t want to work with anyone who I had worked with before in the past, so I kinda wanted to let that die, and just kind of bury it. I felt like if I worked with people that I worked with in the past , it would be too much about us as an ensemble or something, and I wasn’t interested in that. I guess I was sub-consciously looking for new collaborators.

DL: And you two have a history with working with each other right?

AL: After that, I didn’t know Andrea till I went to MacDowell, and we developed a history of working with each other since then. It seems like it was just yesterday, but it actually was four years ago.

AK: My Dinner with Andrea is the second.

D: So, 2013, 2014?

AK: In 2013 we did a piece at The Chocolate Factory that was called, Screening Room, or The Return of Andrea Kleine (As Revealed Through a Re-Enactment of a 1977 Television Program About a ‘Long and Baffling’ Film by Yvonne Rainer.) That whole thing was the title.

DL: That’s a good Fiona Apple album title.

*Everyone laughs*

AL: But, both of us had backgrounds in dance, training in dance and theater.

DL: Are you still working on your novel?

AK: That novel is now going to come out next year, so technically I am still working on it with the last edits.

Michael Kammers and Bobby Privet performing in the lobby. My Dinner with Andrea: the Piece Formally Known as Torture Playlist (2017). New York Live Arts.

Photo: Paul B. Goode, Courtesy of Andrea Kleine

DL: What’s your creative process for writing a novel?

AK: I think I work very intuitively. I look for things to become obsessed about, and then it sort of opens up. But I do think of novels very choreographically in terms of the structure. So, I’m probably less of a wordsmith type of novelist; I’m more interested in the structure of the story. But, I do think about it in terms of performance, in terms of an audience slash reader person reading through the book, like the experience of reading it.

DL: Yeah, I was going to ask, how would you compare the creative process of writing a novel compared to developing a performance piece?

Ak: Well, they’re very different in that I write a novel all by myself, which is fantastic because there is so much less project administration going on, and much less schedule wrangling, and having us meeting. I don’t know if it is less expensive, but it feels less expensive.

AL: It’s emotionally expensive right?… in a different way.

AK: In a way, but writing a novel for me takes some years, two to five years, so it’s a long time sitting for a project, where the work for a performance is very intense, very concentrated in a specific amount of time, and then it’s over, and then you have this sort of postpartum thing. For me the main difference is that in performance, you’re with the audience at the same time, so you’re giving and they’re receiving at the same time, and the with writing, I’m giving, centuries can go by, an then someone gets it all. There’s this huge chasm that’s kind of tragic in a way. In the performance the tragedy is it’s over.

DL: What I’m interested in My Dinner with Andrea is, how did this performance go from being about CIA torture prisons, to being about yourself trying to create that performance? It seems like a large shift in subject matter.

AK: I think part of it is a dodge. I think it was me dodging in a way, taking on that subject. I admit that part of it was a dodge, but I was interested in what the dodge was about. I was also interested in how we are all complicit in all these things going on, and how we all participate in torture. So, my goal was to not let myself off the hook for that, and I felt like taking on this big subject of the torture playlist, but I couldn’t be like, ‘Here’s the torture playlist, isn’t it so fucked up?’ Everyone would be like, ‘Yeah, it is fucked up, okay, see ya tomorrow.’ So, I felt there had to be more subtle incisions in order to open up and shift the prism.

DL: Well, then the performance could be about you dodging that subject, how do you feel about that?

AK: That I dodged it? I don’t know, it was sort of, did I dodge it, or did I take it on? I’d like to think that I did take it on, in that we made people laugh about animals being tortured, and then you realize you laughed about animals being tortured, would you laugh at people being tortured, have you been tortured, or have you tortured someone in some way? So, I don’t see it as an ironic piece. I actually do think I made a piece about torture, but in order to do it, I sort of had to circumvent it and keep spiraling around the issue in making people laugh about it, and sort of making myself a bit ridiculous about it, and sort of pulling the time of the piece out, really stretching it out.

AL: I would like to chime in and say, what I thought was a very shrewd move was bringing the aesthetics of the theater and theatrical training and dance training and the dance world, and that an avant-garde audience is also complicit in a form of torture. It’s clearly different, but I thought that was a shrewd parallel.

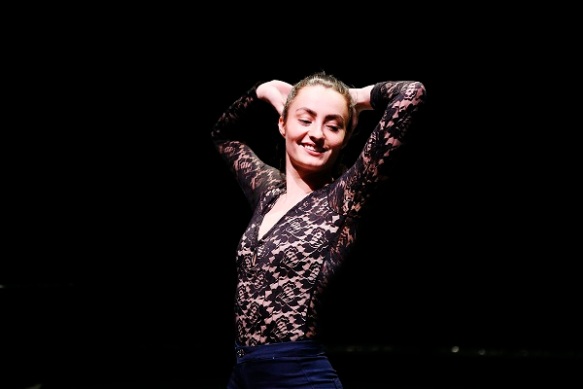

Alison Inglestorm dancing to Call Me Maybe by Carly Rae Jepsen during the second stage of the performance. My Dinner with Andrea: the Piece Formally Known as Torture Playlist (2017). New York Live Arts.

Photo: Paul B. Goode, Courtesy of Andrea Kleine

DL: Thinking about it now, the performance kind of has this idea that asks, instead of talking about torture head on, why do we end up avoiding these hard subjects?

AK: Well, something I was also thinking about was, is there a codified way of making activist work, of making political work, or are we just being complicit if we make politically relevant work and it has to be in this sort of way. I wasn’t interested in that.

In another conversation that we had, Anya said something like, ‘Sometimes I feel like dancers are politically averse in a way.’ And I was also thinking about that, and I was wondering if dance or performance, or choosing the life of a dancer or performance artist by itself is a radical act, an activist act. But, I was also thinking about what you [Anya Liftig] said about theatrical training and also about the David Foster Wallace essay, where he’s like, how do you do it? How do as a person actually throw a lobster into a pot of boiling water, and also, how do these soldiers and military people, how do they do it? How do they actually bring themselves to torture human beings? And then I was thinking of how I have tortured people, asking questions like, did I torture Alison Ingelstrom to do this very technically difficult, long, repetitive dance to this infectious pop song. I don’t know.

So, I was looking at all of these power dynamics, and sort of realizing that there was somewhere a kind of connection between soldiers who are able to torture people and how you were able to put a lobster in boiling water, or you were able to say, ‘Okay, let’s take that again from the top.’

DL: What I find interesting is that these songs like Rawhide, or Call Me Maybe, for us it’s considered pop culture, it’s seen as a source of pleasure and would not be considered torture. Like now in this restaurant, with music playing in the background, it’s just noise, but for someone who has a different religion, or if it is used in a specific way it can be experienced as torture.

AK: Yeah, the songs on the torture list from my understanding were in categories. One was purely volume and aggression, like loud heavy metal music, and in another category were songs that were sexually explicit, and were meant to hurt people from a certain religion. And then, there was this sort of rah rah America category like We are the Champions, and Neil Diamond’s Coming to America. And then there were these cruel earworm jokes like the MeowMix cat food commercial, and the Sesame Street theme song, and Prince’s Raspberry Beret, and there were things like Rawhide which I thought were just cruel because of the lyrics.

AL: Those are bizarre things from a pop culture standpoint right?

Anya Liftig and Andrea Kleine, My Dinner with Andrea: the Piece Formally Known as Torture Playlist (2017). New York Live Arts.

Photo: Paul B. Goode, Courtesy of Andrea Kleine

DL: I want to change the subject a little bit, and I want to talk about a quote from the film, My Dinner with Andre. It comes really early in the beginning, and I felt it was a key line that was significant to understand the nature of the film. William Shawn, who plays himself, recounts how he heard a story about his friend Andre Gregory, who one night broke down crying after hearing the line from the Ingmar Bergman film Autumn Sonata, “I could always live in my art and not in my life.”

Was that quote relevant in the development of this performance? Or, talk about how you think that quote relates to performance in general.

AL: I’m speaking now as an individual performer, and not part of Andrea’s ensemble, but I certainly think for me that’s very true. I think that making work can be a way of avoiding, a way of dealing with, a way of confronting what’s going on in one’s life. I feel very grateful for having discovered performance in the sense that it has made certain things in my life easier to confront. But, I think that living one’s life is hard, and living one’s art can be difficult, but I certainly think living one’s life is harder.

I think of it like Andrea’s notion of the forest, wanting to go running in the forest in terms of that being an expression of my artistic practice, and what I want to do. I want to go running in a way that I’m not capable in my regular life.

AK: Yeah, I have to agree with all of that! *laughs*.

On the flip side of that though, on actually making the piece My Dinner with Andrea, I was trying to figure out also, in some way how to make my life the art. And that was sort of my concept for writing the text.

AL: I want to add that it’s important to note that everything that was said was true. So that moment when I’m describing the lobster performance is one of those moments where there’s this catastrophic conflict between one’s art and one’s life.

Anya Liftig and Andrea Kleine,My Dinner with Andrea: the Piece Formally Known as Torture Playlist (2017). New York Live Arts.

Photo: Paul B. Goode, Courtesy of Andrea Kleine

DL: Okay, let’s get to that. In your conversation with each other in the performance, you talked a lot about how you waste time, your internet habits, and so on. What was it like examining yourself in that way in front of a larger audience in the context of a performance?

AK: In some way I was trying to bring my writing practice and performance practice together. And also, I was trying to some way mirror the film, and how he [Andre Gregory] sort of rambled through the film. It was very intimate in a way and revealing, but because I was performing it with this sort of filter of Andre Gregory, like I was still Andrea in the piece, but I was wearing a costume doing his voice, doing his vocal patterns, wearing that sweater which was really hard to find! That made it sort of easier. It felt like I was being a character, but everything I said was from myself. Which is interesting, because my concerns with theatrical performance are not actorly. I’m not interested in what is considered an actor’s concept of building a character. It’s much more connected to dance, it’s much more connected to choreography. The choreography is Andre Gregory, but the text is me.

DL: What about yourself?

AL: Well, the main thing that I say was the lobster story.

DL: What about in the beginning when you talk about your life as a performance artist and selling things on Etsy?

AL: Oh, yeah, I forgot about the part that I talk about my life and the disasters *laughs*

For me actually the beginning was easier for me to say because I felt those were just facts about my life, and they were in plain view. The part about the lobster was much more of an interior dialogue. It was something where there is information where I said publicly about a lobster performance, but it’s not about that. For me that was an intimate thing to share, much more intimate than saying I’m divorced from a deadbeat etcetera etcetera.

DL: In an interview with Noah Baumbach, Andre Gregory said, “I definitely felt like I was playing someone” rather than himself in this performance, and in an interview with Gene Siskle and Roger Ebert, Shawn and Gregory said, “If we did this again, we would switch roles, just to prove we weren’t playing ourselves.”

Going back to this idea that you [Andrea] were playing Andrea through a filter of Andre Gregory, how much of yourself do you feel came through?

AK: I think the content was all myself, they were all true stories, I was trying to write this book where there was a sub-plot of these animal rights activists, and I was at this retreat in Florida where there were these animal sanctuaries there, but I couldn’t go. I’m actually a very shy performer. I don’t feel like I’m a natural performer in any way. Bobby Previte is a natural performer.

There’s a story that my friends make fun of me, because I has this residency once years ago; this theater company had a place and we were invited to go work on a project. I started to wonder about this woman who I went to junior high school with, and I did performing arts after school with, and is now a very famous Broadway star. But I started to think, ‘I wonder if she’s connected with them, and she’s having gala benefit that we were all invited to, I wonder if she’ll be there? What if she came? I wouldn’t know what to do, I don’t know if I should pretend to be who I am or not.’ This is the line that my friends endlessly make fun of me about, pretending to be who I am.

But, I do all these things to actually convince myself that I can go on stage. And so, being the character Andre Gregory gives me this container to do all that. I’m also not that kind of talker that he is. He’s a famous talker. And it was really weird because someone emailed me afterwards, ‘Oh Andrea I forgot what a raconteur you are.’ I’m like, what the fuck are you talking about? *laughs* I’m very quiet person, I work at a library, I fall asleep at parties. So that part was rather challenging.

Anya Liftig, Andrea Kleine and Alison Inglestorm, My Dinner with Andrea: the Piece Formally Known as Torture Playlist(2017). New York Live Arts.

Photo: Paul B. Goode, Courtesy of Andrea Kleine

DL: Can you talk further about the rituals you go through before a performance?

AK: They’re not rituals like I have to stamp my foot three times before I walk on stage. The sweater was very important to me like I had to have that sweater. I went to so many thrift stores, and it was like what about this sweater, no… that’s too dark that’s too light, it has stripes, it doesn’t have buttons, it had to be the same sweater.

AL: But historically, like in Screening Room…

AK: In Screening Room I played Yvonne Rainer and in that I had a wig. I had a lot more stage anxiety with that one, because I hadn’t performed my own work in over ten years. So, I had to be someone else to get back out there in a way. For Yvonne what got me through it was she was always in motion, she was always nodding her head, bouncing her knee up and down or rocking back and forth, and she always took a big breath before each sentence. So, I could inhabit those things. With Andre Gregory, he had such a particular voice, especially the way he said forest. It was sort of a New York accent from a different generation. It was the word forest that got me into that, like what is the forest and that sent me on that tangent, and that’s what also connected me to Florida, because what are other word like forest? My first line was ‘I was in Florida’, and that’s what kept me in it. There were these werid little nooks in the source material to get me through it.

DL: How about for you [Anya]? You’re mostly reacting to Andrea’s stories in the performance, but did you have any kind of preparation?

AK: A lot of my work is silent, and a lot of my work historically has been about facial movements or about facial gestures. So, I feel that is something I come to pretty naturally. In terms of preparing, it’s kind of interesting, because I wasn’t playing Wallace Shawn, but there is in the dynamic in between Andrea and I as friends, and the person who talks a lot is me. I tend to be a chatter box. So, it was actually nice to sit and listen and be quiet, and to bring that study and training of the face into this choreographic space.

DL: Going back to this idea of Shawn and Gregory switching roles, what do you think the results would be if you two switched roles in this performance?

AK: I think Anya had the more difficult part to be honest.

AL: What would happen? I would probably just go off and blabber on and on incoherently. Not that you were incoherent, but I would be incoherent, an not as interesting. *laughs*

What I really loved was listening to Andrea’s dialogue many many times, because I felt like every time I heard it, something else jumped out at me in terms of another connection. There was a serious of coincidence, like that fact that you’re from Richmond, and you knew this person. Like they’re so vague, but amazing synchronicities, and I was like, is it made up? It seemed so fantastical that it may have been made up.

DL: I wanted to get to this quote you said at the end of your interview with each other. When referring to Lucy Grealy’s Autobiography of a Face, you stated, “For me when I was reading that, I had never written ‘memoir.’ I had never written about myself, but it seemed when she said that, it wasn’t that she was dishonest about it, but perhaps the story of one’s life is dishonest. It is actually just the way you remember it or the way you write it.”

Can you talk further about that? I took that as relating to performance where as an audience member you often take for granted that what you are seeing isn’t what is actually happening. Meaning, the audience applies meaning to the actions of a performer regardless if those meanings are true or not. Can a performer truly be honest?

AL: I think it can be a version of honesty. I think there is truth there, but what I was specifically talking about in that quote was, in terms of truth or veracity, I primarily worked without words for a very long time, because I felt I was trying to make a more open vessel for performance, and that words would be too specific or alienating in some way.

And, there has been some shift where I’ve been writing quite a bit for the past two years and discovering that the more specific I think the words are and the more specific the experience is, perhaps the more open it might be. I think one is always becoming on stage. To me that’s what’s exciting about performance as well as being a performer is I am discovering something and changing in front of people. That’s my ideal, where I am discovering something when other people are hopefully are, and that act of becoming is something that can be witnessed.

AK: I think the act of becoming and what you were trying to say in going back to that quote, is that, just practicing in the act of becoming on stage, there’s quite a lot of work that goes into that, work, and concepts, and practice. I think that was part of what Lucy Grealy was saying. I think people sometimes think that when you write a memoir or something autobiographical, it’s like opening the filing cabinet in your brain and you’re just transcribing a memory, when really, writing and artwork is far more involved and complex than that. There’s a memory you may have in your childhood, but what does it mean, and how do you re-inhabit it, and why would you re-inhabit it, what else is there?

Andrea Kleine, Anya Liftig and Alison Inglestorm, My Dinner with Andrea: the Piece Formally Known as Torture Playlist(2017). New York Live Arts.

Photo: Paul B. Goode, Courtesy of Andrea Kleine

DL: I brought this up because when watching My Dinner with Andrea, and going back to your lobster story, I recalled having previously heard a different version of that story, where someone took it and threw it in the sea. And so during the performance, I didn’t think you were telling a real story. That’s why I was so surprised to hear that it was in fact true. So, my misunderstanding led to me believing a truth that was not actually true.

AL: That’s interesting. The lobster performance where it was stolen and taken and released under the bed of stars into the sea—it directly led to this other iteration of the performance. Because the performance was interrupted I was asked to go through with the performance. And that was part of the second performance where I actually cooked the lobster and eat it, and that really had to happen in order to complete it. So there wouldn’t be one without the other.

DL: I want to talk about durational performances. Watching the movie My Dinner with Andre, it feels like a shaggy dog story, where it sounds like you’re hearing these profound ideas about life, but at the end there really isn’t a resolution. The subject of the movie is quite mundane: it’s two people talking over dinner. Andre Gregory in the film even makes the point of being tired of these mundane experiences in life, but as a viewer, this is itself a mundane experience.

How did bringing this long durational action add to this performance?

AK: That goes back to the idea of, can I make a piece about torture? And, of course one of the concepts of torture is a manipulation of time, and the person inflicting the torture has to make them feel like this is going to go on forever. So, I was interested in that with the long opening solo by Alison, and I was interested in the very long two-hour dinner conversation from the movie.

I thought it was interesting, because of course your fascinated by this eccentric character. The Wally character is like I’m just living this mundane life as a playwright, and Gregory is off going to beehives and to the Sahara [desert]. But, towards the end of the film Wally pushes back a bit, and Andre disavows things, and Wally asks ‘How can you disavow that?’ and they come back together and leave. Nothing is resolved and I love that because I hate conventional resolution, and nothing was resolved in My Dinner with Andrea, it just ended. I didn’t want one last speech; it was up to the audience to decide.

The ending was interesting being on stage because the light was these A Chorus Line finale footlights on steroids coming at the audience. It was blinding the audience, but from where we were on stage, it was lighting up the audience from our point of view. Then there was this saxophone solo that was in a way emotionally manipulative and nostalgic in a way, and things are crescendoing, and then we just leave, leaving the audience to subjectively sort out that material.